Historic telegrams found at union

Recently, a union staff member discovered four historic telegrams further documenting our union's early and consistent involvement in the civil rights movement. The four telegrams dating back to March 1965 are in excellent condition and were found by chance in a bound volume of issues of the Hotel, Motel and Club Voice, a magazine published at the time by Local 6 for its members. The telegrams were sent by our union at the request of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. after the murder, in Selma, Alabama, of Rev. James Reeb by a racist white mob.

During March 1965, three civil rights marches in Selma, Alabama, transfixed and ultimately transformed our country, paving the way for the passage of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Among the many struggles ongoing during this period, African-Americans of courage and principle had been risking their lives to turn their right to vote into a reality. Blacks had been systematically deprived of the vote through a variety of means, including Jim Crow laws, intimidation and threats, violent physical assaults and beatings, and murder.

Disenfranchisement of black voters was widespread. Efforts to counter it took deep hold in Selma. A Library of Congress historical note recalled that African-Americans accounted for more than half of the city's population but only about two per cent of its registered voters. As the efforts of voting rights campaigners intensified in Selma, racist whites, including local police and state troopers, responded to the campaigners' peaceful protests with increasing aggressiveness, culminating in the February 1965 shooting death of 26-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson.

To protest Mr. Jackson's killing and the continuing suppression of the voting rights of black Americans, civil rights campaigners set out from Selma on Sunday, March 7, to march to Montgomery, the state capitol. John Lewis, the 25-year-old chairperson of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and Hosea Williams, a 39-year-old World War II veteran, civil rights activist, and a leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led the march.

According to a report in the New York Times of March 8, 1965, the group of some 525 demonstrators had walked slowly and silently, two abreast, across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the outskirts of Selma. Upon crossing the bridge, they were confronted by a line of state troopers, local police officers, and other white males that spanned the entire width of the divided four-lane highway. They were commanded to stop and then told they "constituted an unlawful assembly" and had "two minutes to turn around and go back to your church."

When they did not do so, the officer in charge of the troopers ordered, "Troopers, advance.'"

Scores of photographs and chilling pieces of television footage memorialized what the Times described as the "swift and thorough" suppression of the march. The images live on: white men supposedly responsible for enforcing the law wielded tear gas, nightsticks, and whips in a frenzy of brutality, all of it directed against civil rights demonstrators engaged in a peaceful demonstration to protest the continued denial of the right of African-Americans to vote.

By the following day, March 8, people throughout the United States and in countries around the world had been riveted and repulsed by the brutal conduct of the state's troopers, its police, and the white male volunteers the sheriff had called into action and specially deputized.

The outrage escalated when Rev. Reeb was severely beaten by several local white males after a second protest march Dr. King led in Selma on March 9. Rev. Reeb had traveled from Massachusetts to Selma to lend his support to the voting rights demonstrators. He died two days later from the injuries sustained in the beating. Reeb's assailants, though their identities were known, were never brought to justice.

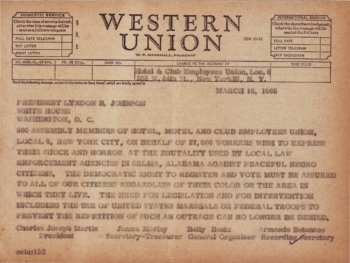

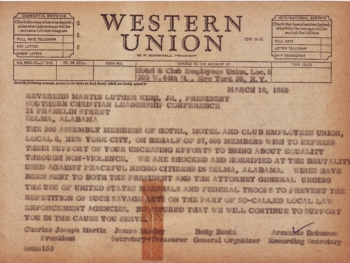

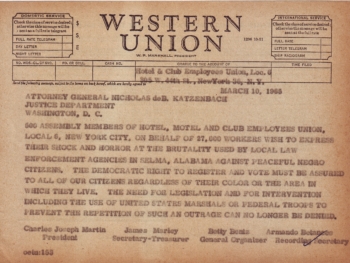

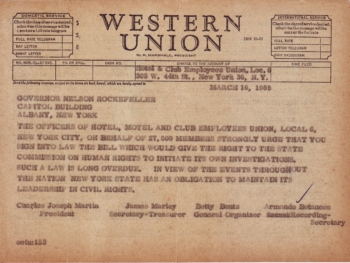

The union sent three of the four telegrams recently discovered on March 10, 1965. They were sent to President Lyndon B. Johnson, Attorney General Nicholas deB. Katzenbach, and to Dr. King, the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The union sent the fourth telegram to New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller a few days later, urging him to sign into law a bill that would strengthen the state's Commission on Human Rights by empowering it to initiate its own investigations.

The union's telegrams to the President and the Attorney General condemned the brutality law enforcement agencies in Selma had directed against peaceful Black citizens, asserted that the right to register and vote must be assured to all citizens, and further asserted that legislation and, if necessary, federal marshals or troops must be used to prevent any further such outrages from occurring. The telegram to Dr. King also expressed the union's shock and horror at the brutality used against peaceful Black citizens in Selma and advised him of the union's telegrams to the President and the Attorney General. It ended with a sentiment the union would have already expressed to Dr. King many times: "Be assured that we will continue to support you in the cause you serve."

These four telegrams attest to our union's continuous readiness to fight to protect and defend civil rights. The union has always been an advocate for the fair and equal treatment of all of our members. It had fought early on for a no discrimination clause in the union contract and to do away with hotels' racially-based disparities in pay.

And even before Dr. King commanded a national following, our union lent its support to his various campaigns and initiatives. Union officers and members, and their family members, were frequent participants in civil rights rallies and demonstrations, including those in Washington, D.C., and the union consistently played an important role in the fights to pass important civil rights statutes.

All four telegrams are important reminders not only of our union's historical commitment to the protection and defense of civil rights but also of our ongoing responsibility to maintain the continuity of that commitment. It has become apparent in the months that have elapsed since the November 2010 elections that attacks on civil rights are currently resurgent at every level of government. Past generations fought to protect the right to register and vote. Now, just short of fifty years later, voting rights are again under attack, and pitched battles over the enactment of new types of voter suppression legislation are ongoing in legislatures and courts throughout the country, including in Florida, Texas, and Wisconsin.

The telegrams will keep reminding us of that which we must never forget: that we owe a debt to the generations of HTC members who fought hard for the rights we enjoy today and that we, in turn, have an obligation to fight hard to protect these rights for future generations.

To learn more about the March on Selma, visit the resources below:

Reed, Roy. Alabama Police Use Gas and Clubs to Rout Negroes. New York Times. March 7, 1965.

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle.

The Library of Congress. American Memory - Today in History: March 7, First March from Selma.